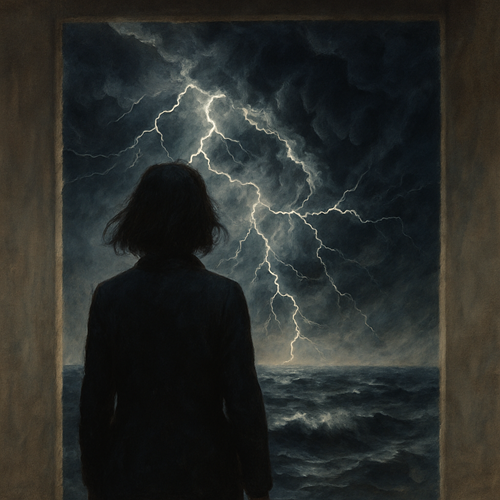

You dream every night — even if you don’t always remember. Yet for centuries, people have asked the same two questions: What are dreams, and what do they mean?

This article traces how interpretations of dreams have evolved through three major shifts — each offering a more human, more personal way of understanding what’s happening inside you at night. The journey leads to today's most powerful perspective: Process-Oriented Dreamwork. As you read, you may recognize yourself in these ideas — and perhaps discover new ways to explore your own dreams.

Before Freud — Dreams in the Scientific Mind

The interpretation of dreams has been evolving for centuries. While there's a rich and vital world of how Indigenous and non-Western cultures have understood dreams — full of symbolism, spirituality, and communal meaning — that will be explored in future articles. For now, let’s briefly focus on the scientific view in Europe before Freud.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, European science had largely dismissed dreams as random, meaningless leftovers from the day. Enlightenment thinkers leaned hard into logic and reason, and in that light, dreams looked chaotic and useless. Some doctors thought they were caused by bad digestion or illness. Others believed they were just noise from the nervous system. Few saw dreams as worth listening to. They were ghostly, flickering things — not real, not useful.

And then came Freud.

Step 1: The Freudian Paradigm — Dreams as Disguised Desires

Freud looked at dreams and said: these strange stories aren’t nonsense — they’re full of meaning. They’re your hidden desires, sneaking out at night. You may not admit these desires during the day, but they find ways to express themselves while you sleep, often through symbols and disguises.

You might dream of being in a crowded elevator that suddenly starts falling. Freud might say: you’re not just afraid of elevators — this is about losing control. Maybe it connects to childhood fears or desires that still live inside you, unspoken and unresolved.

This was a breakthrough! Suddenly, dreams turned from meaningless chaos into something powerful — a direct connection to the hidden parts of your inner life. For the first time, psychology treated dreams as serious material — something to work with, something that could help heal.

But Freud's system could feel narrow. He often traced everything back to early trauma, sexuality, or repression. If your dream didn’t seem to fit the theory, it was easy to feel like you were wrong — or broken. Not every dream wants to be decoded like a locked vault. Sometimes you just want to feel seen, not analyzed.

Step 2: The Jungian Expansion — Dreams as Archetypal and Transformational

Jung looked at dreams and saw not just desire, but mystery. He believed your dreams come from a deeper place — not just your personal story, but a shared inner world full of ancient symbols and patterns. This is the collective unconscious, and it’s alive in you, whether you know it or not.

You might dream of walking through a dark forest and meeting a wise old woman who gives you a key. Jung would say: this isn’t just a strange scene — it’s a message from your deeper self. The forest might represent the unknown inside you. The woman could be the archetype of inner wisdom. The key? Maybe it’s the start of a transformation.

Jung encouraged you to draw your dreams, talk to your dream characters, and let them speak back. Dreams weren’t just clues — they were companions on your path to becoming whole.

This approach opened up a world where your dreams could feel sacred, personal, and meaningful in ways that stretched beyond logic. You were no longer just solving a problem — you were stepping into a story that was bigger than you.

But there was a catch. Jungian work often lived in the realm of symbols and theory. If you weren’t steeped in archetypes or mythology, it could be hard to connect. You might find yourself asking: this is beautiful — but what do I actually do with it?

Step 3: The Process-Oriented Turn — Dreams as Living Experiences

Then came a shift. What if your dream isn’t just something to interpret — what if it’s something to experience? That’s the heart of Process-Oriented Psychology, developed by Arnold Mindell.

Here, your dream is still alive — not just while you’re sleeping, but right now, in your body, in your emotions, in the way you move or hold tension.

You might dream that you’re trying to speak, but no sound comes out. Instead of asking what it means, you lean into it. What does your throat feel like right now? Can you let your body express that silence? Maybe you feel tightness, or sadness, or a kind of pressure that has no words. Suddenly, a memory comes. A time when you weren’t allowed to speak your truth. Now the dream isn’t just an image — it’s a doorway. And you’re stepping through it.

Mindell also spoke of the Dreammaker — the deep intelligence that creates your dreams and your waking struggles, nudging you toward wholeness.

This approach brought dreams into the body. You don’t need a dictionary or a guru. You just need to feel what’s already happening. Instead of interpreting the dream, you let it move through you. You become it.

Of course, this takes practice. It can feel strange at first. You might not know how to start. But once you do — once you let your dream breathe through your voice or hands or heartbeat — something shifts. You don’t just understand the dream. You change with it.

Conclusion: The Future Is Already Dreaming You

Each step in dreamwork has pulled the curtain back a little further:

-

Freud showed you that dreams matter.

-

Jung showed you that they have wisdom.

-

Mindell shows you that they live in you.

You’re not just a decoder, sitting outside your dream, trying to crack the code. You’re a participant. A dreamer who can listen, move, feel, and become. You don’t need to find the "right" interpretation. You just need to follow the thread of experience.

And maybe the real question isn’t "What does this dream mean?" Maybe it’s:

What is this dream becoming — and who am I becoming with it?